4 Running programs on remote computers and retrieving the results

This two hour workshop will show attendees how to use remote computers to run their analyses, work with the output files, and copy the results back to their laptop and desktop computers. We will discuss input and output formats, where files are usually read from and written to, and how to use the ssh software to copy files to and from remote computers.

In workshop 4, we will do more with running remote commands, getting files onto your remote system, file permissions, and actually working effectively on remote systems. We will also talk a bit about processes and other aspects of multiuser systems.

4.1 Using SSH private/public key pairs

Today we’re going to start by using a different way to log in - ssh key pairs.

Key pairs are a different way to provide access, and they rely on some mathematical magic called asymmetric cryptography or public-key cryptography (see wikipedia). (The details are far beyond the scope of this lesson, but it’s a fascinating read!)

There are two parts to key pairs - the private part, which you keep private; and the public part, which you can post publicly. Anyone with the public key can challenge you to verify that you have the private key, and only the person with the private key can verify, so it’s a way to “prove” your identity and access. (The same idea can be used to sign e-mails!)

Key pairs solve some of the problems with passwords. In brief,

- they are (much!) harder to guess than passwords.

- key pairs enable programs to do things without you having to type in your password.

- the private part of a key pair is NEVER shared, unlike with passwords where you have to type the password in.

- but the public part of pair can be shared widely.

Because of these features, some systems demand that you use them. Farm is (usually) one of them; we have a special exception for the datalab-XX accounts, because key pairs are a confusing concept to teach right off the bat.

4.2 Mac OS X and Linux: Using ssh private keys to log in

Your private key for your datalab-XX account is kept in .ssh/id_rsa.

We need to copy it locally to make use of it.

Run the following command in your Terminal window:

cd ~/

scp datalab-XX@farm.cse.ucdavis.edu:.ssh/id_rsa datalab.pemand then

chmod og-rwx datalab.pem(we’ll explain the second command below!)

datalab.pem is your private key pair!

Now, to log into farm using the key pair, run

ssh -i datalab.pem datalab-XX@farm.cse.ucdavis.eduand voila, you are in!

(VICTORY!)

You’ll need to keep track of your datalab.pem file. I recommend keeping it in your home directory for now, which is where we downloaded it.

4.3 Windows/MobaXterm: Using ssh private keys to log in

For MobaXterm, connect as you did in workshop 3 and download .ssh/id_rsa to some location on your

computer, named datalab.pem.

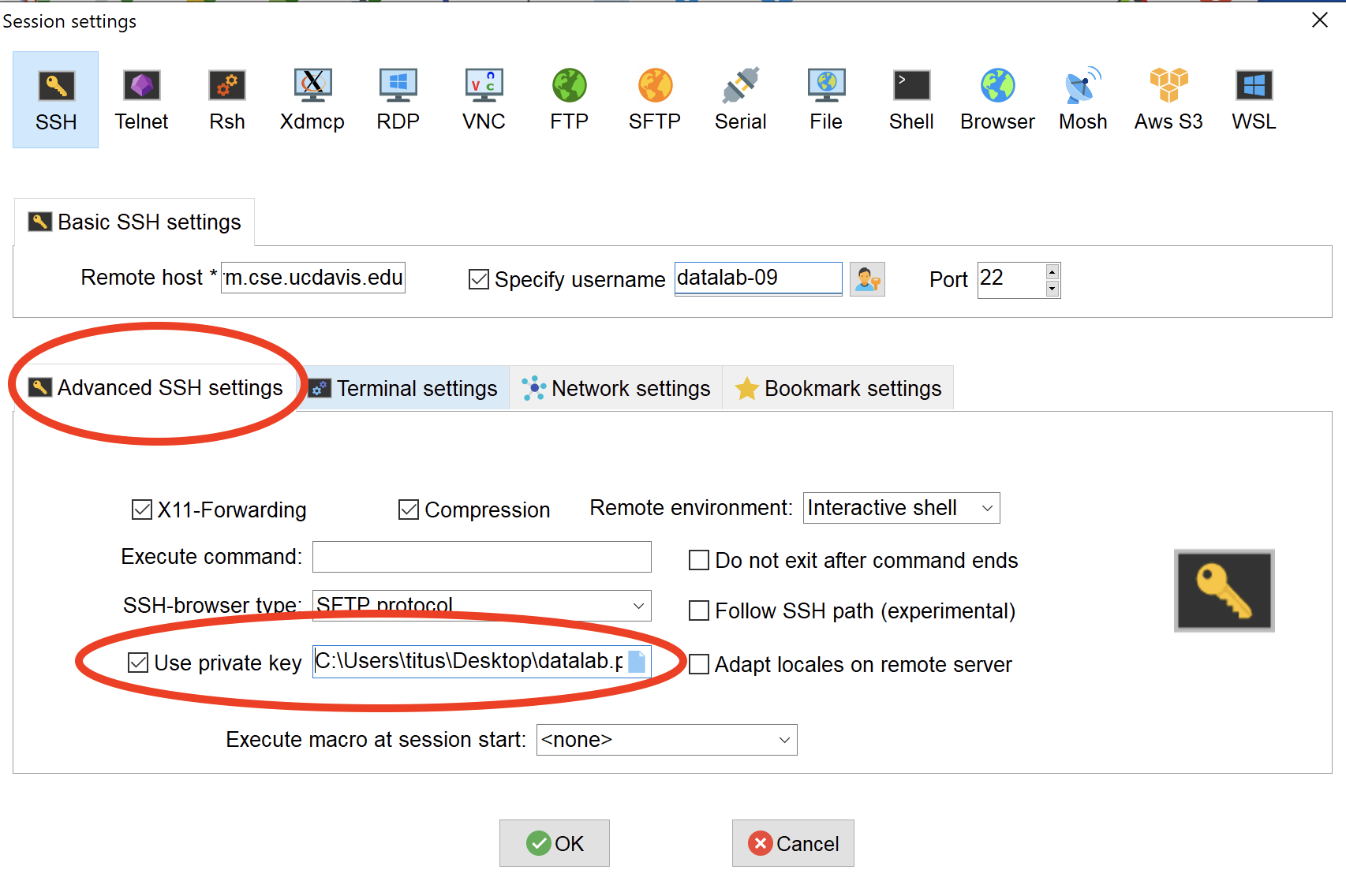

Now, create a new session and go to “Advanced SSH options” and select it the private key pair (see screenshot).

Now connect.

Voila! No password needed!

VICTORY!!

Note that if you change the location of your private key file, you’ll need to go find it again :).

4.4 Some tips on your private key

NEVER SHARE YOUR PRIVATE KEY.

We’ll talk more about private key management in the future, but the basic idea is that you should create a new private key for each computer you are using, and only share the public key from that computer.

4.5 Working on farm

So farm is a shared computer with persistent storage (which is typical of a remote workstation or campus compute cluster (HPC). This means a few different things!

Let’s start by logging back into farm. (You got this!)

4.5.1 First, download some files:

Let’s make sure you have the right set of files from the last workshop – this will take the set of files here and make them appear in your farm account:

cd ~/

git clone https://github.com/ngs-docs/2021-remote-computing-binder/(If you’ve already done this, you can run this again and it will just fail, and that’s fine.)

4.5.2 Configuring your account on login

One thing you can do is configure your account on login the way you want.

This typically involves configuring your login shell. The shell we’re using

is bash, and it runs the .bash_profile

text file on login.

Let’s add a ‘hello’ message!

Edit the file ~/.bash_profile, e.g. with nano:

nano ~/.bash_profileand type echo Hello and welcome to farm at the top of the file.

If using nano, save with CTRL-X, say “yes” to save, hit ENTER.

Now log out and log back in.

You should now see ‘Hello and welcome to farm’ every time you log in! (You can easily delete it too, if you find it annoying :)

The commands in .bash_profile are run every time you log in; there’s

also a file called .bashrc that is run for every shell, not just login shells.

There are two important differences between .bash_profile and

.bashrc.

FIRST, .bash_profile is run only on login, while .bashrc is

run every time a shell starts. So you can add commands like this:

alias lf='ls -FC'

to your .bashrc if you want to have the lf command available at every

shell; we’ll cover more configuration commands in

workshop 6

and beyond.

SECOND, .bashrc should not output anything via echo (or any

other command), as that will

prevent the scp file copy command from working.

When editing these files, you can see changes without having to log out and log back in using the source command. If you add the alias command above

into your .bashrc, you can test it out like so:

source ~/.bashrcand now lf will automatically run ls with your favorite options.

For another example, here you could make rm ask you for confirmation

when deleting files:

alias rm='rm -i'CHALLENGE QUESTION: Create an alias of hellow that prints out

hello, world and add it to your .bashrc; verify that it works!

4.6 Using multiple terminals

You don’t have to be logged in just once.

On Mac OS X, you can use Command-N to open a new Terminal window, and then ssh into farm from that window too.

On Windows, you can open a new connection from MobaXterm simply by double clicking your current session under “User sessions.”

What you’ll end up with are different command-line prompts on the same underlying system.

They share:

- directory and file access (filesystem)

- access to run the same programs, potentially at the same time

They do not have the same:

- current working directory (

pwd) - running programs, and stdin and stdout (e.g.

lsin one will not go to the other)

These are essentially different sessions on the same computer, much like you might have multiple folders or applications open on your Mac or Windows machine.

You can log out of one independently of the other, as well.

And you can have as many terminal connections as you want! You just have to figure out how to manage them :).

CHALLENGE: Open two terminals logged into farm simultaneously - let’s call them A and B.

In A, create a file named ~/hello.txt, and add some text to it. (You

can use an editor like nano, or you can use echo with a redirect,

for example. If you use an editor, remember to save and exit!)

In B, view the contents of ~/hello.txt. (You can use cat or less

or an editor to do so.)

A tricky thing here is that B does not necessarily have a way to know that you’re editing a file in A. So you have to be sure to save what you’re doing in one window, before trying to work with it in the other.

We’ll cover more of how to work in multiple shell sessions in workshop 7 and later.

4.6.1 Who am I and where am I running!?

If you start using remote computers frequently, you may end up logging into several different computers and have several different sessions open at the same time. This can get …confusing! (We’ll show you a particularly neat way to confuse yourself in workshop 7!)

There are several ways to help track where you are and what you’re doing.

One is via the command prompt. You’ll notice that on farm, the command prompt contains three pieces of information by default: your username, the machine name (‘farm’), and your current working directory! This is precisely so that you can look at a terminal window and have some idea of where you’re running.

You might also find the following commands useful:

This command will give you your current username:

whoamiand this command will give you the name of the machine you’re logged into:

hostnameThese can be useful when you get confused about where you are and who you’re logged in as :)

4.6.2 Looking at what’s running

You can use the ps command to see what your account, and other accounts,

are running:

ps -u datalab-09This lists all of the different programs being run by that user, across all their shell sessions.

The key column here is the last one, which tells you what program is running under that process.

You can also get a sort of “leaderboard” for what’s going on on the shared computer by running

top(use ‘q’ to exit).

This gives a lot of information about running processes, sorted by who is

using the most CPU time. If the system is really slow, it may be because

one or more people are running a lot of things, and top will help you

figure out if that’s the problem. (Another problem could be if a lot of

people are downloading things simultaneously, like we did in

workshop 3; and yet another

problem that is much harder to diagnose could be that one or more people

are writing a lot to the disk.)

This is one of the consequences of having a shared system. You have access to extra compute, disk, and software that’s managed by professionals (yay!), but you also have to deal with other users (boo!) who may be competing with you for resources. We’ll talk more about this when we come to workshop 10, where we talk about bigger analyses and the SLURM system for making use of compute clusters by reserving or scheduling compute.

If performance problems persist for more than a few minutes, it can be a good idea to e-mail the systems administrators, so that they are alerted to the problem. How to do so is individual on each computer system.

On that note –

4.6.3 E-mailing the systems administrators

When sending an e-mail to support about problems you’re having with a system, it’s really helpful if you include:

- your username and the system you’re working on

- the program or command you’re trying to use, together with as much information about it as possible (version, command line, etc.)

- what you’re trying to do and what’s going wrong (“I’m trying to log in from my laptop to farm on the account datalab-06, and it’s saying ‘connection closed’.”)

- a screenshot or copy/paste of the confusing behavior

- a thank you

This information is all useful because they deal with dozens of users a day, and may be managing many systems, and may not be directly familiar with the software you’re using. So the more information you can provide the better!

4.8 Disk space, file size, and temporary files

You can see how much free disk space you have in the current directory with this command:

df -h .You can see how much disk space a directory is using with du:

du -sh ~/I highly recommend using /tmp for small temporary files. For bigger

files that you might want to persist but only need on one particular

system, there is often a location called /scratch where you can make

a directory for yourself and store things. We’ll talk more about that

in workshop

10.

Finally, the command

freewill show you how much system memory is available and being used.

This command:

cat /proc/cpuinfowill give you far too much information about what processors are available.

Again, we’ll talk more about this in workshop 10 :).

4.9 Summing things up

In this workshop, we talked a fair bit about working on shared systems, setting permissions on files, transferring files around, and otherwise being effective with using remote computers to do things.

In workshop 5, we’ll show you how to customize your software environment so you can do the specific work you want to do. We’ll use CSV files, R, and some bioinformatics tools as examples.